With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union, America found itself without an arch nemesis for the first time in 90 years and in 1991, the "lone superpower" led a coalition of 540,000 soldiers in driving Saddam Hussein from Kuwait but unfortunately for the world, the dictator was left in power. George H.W. Bush enjoyed a brief few months of popularity and less than two years later, was turned out of office by an unknown governor from Arkansas. The inevitable job of deposing Saddam was left to future leaders as Americans debated the size of its military and intelligence gathering requirements.

Bill Clinton and the Democrats wished to cash in the “peace dividend” by downsizing US military and intelligence programs. To many, the military came to be seen as a peace-keeping force to be used for humanitarian purposes. Kosovo, Haiti, and Somalia were seen by Republicans and Conservatives as unnecessary to the vital interests of the United States while Democrats were inclined to intervene in world humanitarian crises. The Republicans along with the military itself resisted the "police role" but the pendulum swung toward a smaller military designed to react to global hotspots and shorter engagements rather than the previously perceived threat of a world war. George Bush came to office in 2001 as being opposed to “nation building” but it wasn’t long before fate sprung an ambush on a nation unprepared and ill-suited for empire building.

Not much changed in this basic approach until the fall of former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and the ensuing debacle in Iraq. The military's top brass and the Pentagon continued to view everything in black and white. For them, there was a clear distinction between combat missions and the tools and mechanics of war, on the one hand, and the peacekeeping missions, on the other. The latter were multinational and had a decidedly civilian flavor, and consisted of things like providing policing for nation-building in Kosovo -- not exactly something that was particularly appealing to the US military.

The notion that the world's most modern and powerful military machine could end up struggling to gain the upper hand over scattered insurgents was inconceivable and hit the US military like an earthquake. Until a few years ago, no one in the US military would have believed that instead of dropping bombs and engaging in fierce combat, it would one day be drilling wells, directing traffic, building schools and organizing local elections -- and that it would be doing all of these things not after but in the middle of a war. Finally, no one would have imagined that these civilian tools would end up being described as the most-effective weapons on the road to victory.

"In Bosnia, we had a feeling for the first time that perhaps we are poorly prepared after all," says Dennis Tighe, a slim, jovial man who wears wide suspenders over his shirt. Tighe, a young-looking 60, is in charge of maneuvers and troop exercises for officers at Fort Leavenworth -- Combined Arms Center Training, or CAC-T in short.

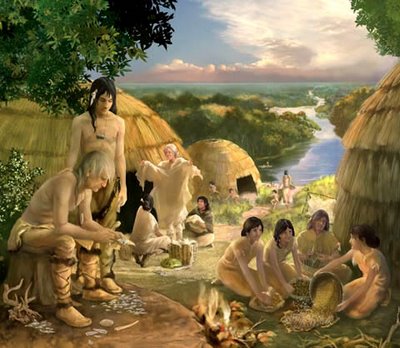

In the former Yugoslavia, says Tighe, the US military was unprepared for the confusion of scattered small battles. It had trouble dealing with a conflict that was so culturally charged, a war without fronts and battle lines in tiny countries whose problems the Americans found deeply puzzling. The military also failed to realize that rebuilding stadiums could sometimes be more important than winning minor military skirmishes. It also had trouble understanding something that organizations like the United Nations had long known, and that is that providing seeds for crops can ultimately be more critical to achieving success than ammunition. It took time, especially for a military that had been exposed to doctrines set in stone for so many decades, until new ideas were allowed to penetrate into its ranks.

The courage to question

It took commanders who could implement changes and who had the courage to question the Pentagon's old-school way of thinking and its approach to the war in Iraq. The process began in Leavenworth, in 2004, with William Wallace, the general who had commanded the US Army's "Thunder Run" to Baghdad in the initial stage of the war. But once it became increasingly evident that Iraq was in turmoil, Wallace began to doubt his own hard-hitting strategy and reinterpret the operation's successes and failures. As it turned out, Wallace was the first to question all the military doctrines that had been in place until then. His direct successor is currently in the process of eliminating them altogether.

David Petraeus, a three-star general who completed his own officer-training program at Fort Leavenworth and graduated at the top of his class of 1,000, has been in charge at the facility since the autumn of 2005. When he was in command of the 101st Airborne Division as they advanced northward through Iraq up to Mosul, Petraeus already held a doctorate in political science. Today, at Leavenworth, he serves as a professor in combat gear.

Bad News for DinosaursLacking the proper support from the rest of government, the Military set about building their own version of the State Department, the FBI and the Peace Corps.

Petraeus is the man at the helm of the Army's top-down revolution. Together with a general from the US Marines, James Mattis, he has written a new doctrine on counterinsurgency, a doctrine that turns almost every previous rule of warfare on its head.

The 241-page document contains an outline of the history of all rebellions and a guide to the wars of the future. For the first time, it draws no distinction between civilian and classic military operations. In fact, it almost equates the importance of the two. Petraeus believes that the military can no longer win wars with military might alone. On the contrary, according to the new theory, it must do its utmost to avoid large-scale destruction and, by as early as the initial attack, not only protect the civilian population but also support it with all available means in order to secure its cooperation for regime change. As uncomplicated as it may seem, Petraeus's new doctrine represents a sea change when it comes to the US military's training and combat procedures. Some might also interpret it as a way of settling scores with the failed strategy in Iraq.

Fate has played a cruelly, ironic trick on America in Iraq and the resulting 180-degree polar shift in politics and attitudes could affect the world for decades and generations. It seems very likely that the Pentagon's attitude adjustment has come too late and the effort of Petraeus and associates could soon be relegated to forgotten, dusty library shelves.